The ‘Kvetera Interpretation Trail’ project was implemented within the framework of the EU4ITD –Catalyst for Economic and Social Life (CESL) project and funded by the European Union and the German government.

The ‘interpretive trail’ project also involved development of a digital brochure designed to revive the significant historical events that unfolded on the lands of Akhmeta and highlight region’s rich cultural heritage, biodiversity, and captivating stories of intangible legacy. Readers will encounter remarkable examples of heroism, devotion, and patriotism that have earned an honored place in Georgian oral mythology, poetry, and folklore.

Akhmeta’s tourism guidebook introduces readers to remarkable episodes of history, cultural heritage sites, and stories of folk artistry and daily life shaped over the centuries.

Through the interpretive boards and the guidebook, visitors and readers can embark on a journey across Akhmeta Municipality—a region known for its rich history, distinct identity, and vibrant ethnic and cultural tapestry.

The materials created within this project encapsulate a heritage that showcases the finest examples ofhuman coexistence with nature. They also recount warrior-like past and the enduring cycle of life that has fostered a unique cultural heritage amidst challenges and resilience.

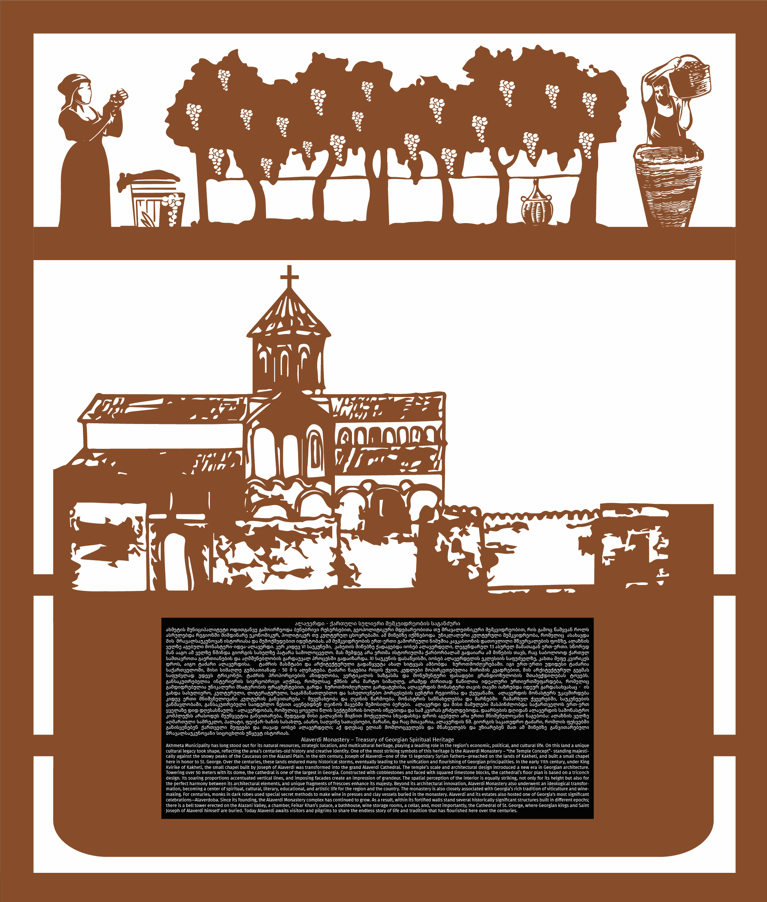

Alaverdi Monastery – Treasury of Georgian Spiritual Heritage

Akhmeta Municipality has long stood out for its natural resources, strategic location, and multicultural heritage, playing a leading role in the region’s economic, political, and cultural life. On this land a unique cultural legacy took shape, reflecting the area’s centuries-old history and creative identity. One of the most striking symbols of this heritage is the Alaverdi Monastery – “the Temple Concept”- standing majestically against the snowy peaks of the Caucasus on the Alazani Plain. In the 6th century, Joseph of Alaverdi—one of the 13 legendary Syrian Fathers—preached on the lands of Kakheti, and built a small chapel here in honor to St. George. Over the centuries, these lands endured many historical storms, eventually leading to the unification and flourishing of Georgian principalities. In the early 11th century, under King Kvirike of Kakheti, the small chapel built by Joseph of Alaverdi was transformed into the grand Alaverdi Cathedral. The temple’s scale and architectural design introduced a new era in Georgian architecture. Towering over 50 meters with its dome, the cathedral is one of the largest in Georgia. Constructed with cobblestones and faced with squared limestone blocks, the cathedral’s floor plan is based on a triconch design. Its soaring proportions, accentuated vertical lines and imposing facades create an impression of grandeur. The spatial perception of the interior is equally striking, not only for its height but also for the perfect harmony between its architectural elements, and unique fragments of frescoes enhance its majesty. Beyond its architectural innovation, Alaverdi Monastery also underwent an ideological transformation, becoming a centre of spiritual, cultural, literary, educational, and artistic life for the region and the country. The monastery is also closely associated with Georgia’s rich tradition of viticulture and winemaking. For centuries, monks in dark robes used special secret methods to make wine in presses and clay vessels buried in the monastery. Alaverdi and its estates also hosted one of Georgia’s most significant celebrations—Alaverdoba. Starting in late September and lasting three weeks, this festival attracted between 15,000 and 20,000 pilgrims from across the region. Since its founding, the Alaverdi Monastery complex has continued to grow. As a result, within its fortified walls stand several historically significant structures built in different epochs; there are: a bell tower erected on the Alazani Valley, a chamber, Feikar Khan’s palace, a bathhouse, wine storage rooms, a cellar, and, most importantly, the Cathedral of St. George, where Georgian kings and Saint Joseph of Alaverdi himself are buried. Today Alaverdi awaits visitors and pilgrims to share the endless story of life and tradition that has flourished here over the centuries.

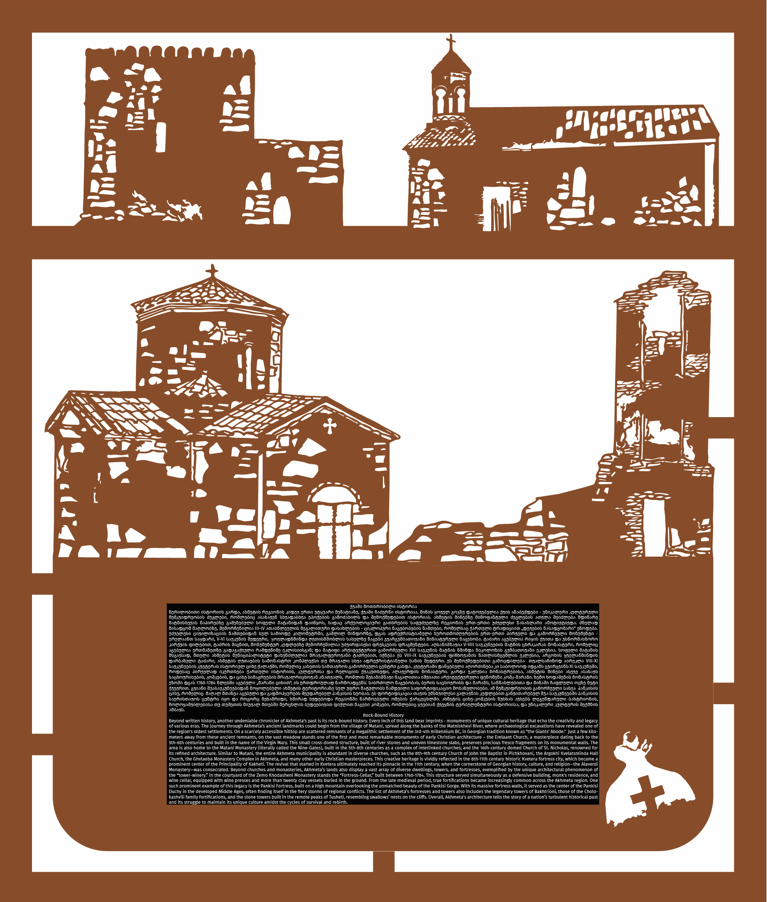

Rock-Bound History

Beyond written history, another undeniable chronicler of Akhmeta’s past is its rock-bound history. Every inch of this land bear imprints – monuments of unique cultural heritage that echo the creativity and legacy of various eras. The journey through Akhmeta’s ancient landmarks could begin from the village of Matani, spread along the banks of the Matniskhevi River, where archaeological excavations have revealed one of the region’s oldest settlements. On a scarcely accessible hilltop are scattered remnants of a megalithic settlement of the 3rd-4th millennium BC, in Georgian tradition known as “the Giants’ Abode.” Just a few kilometers away from these ancient remnants, on the vast meadow stands one of the first and most remarkable monuments of early Christian architecture – the Erelaant Church, a masterpiece dating back to the 5th-6th centuries and built in the name of the Virgin Mary. This small cross-domed structure, built of river stones and uneven limestone slabs, preserves precious fresco fragments on its monumental walls. The area is also home to the Matani Monastery (literally called the Nine-Gates), built in the 5th-8th centuries as a complex of interlinked churches; and the 16th-century domed Church of St. Nicholas, renowned for its refined architecture. Similar to Matani, the entire Akhmeta municipality is abundant in diverse churches, such as the 8th-9th century Church of John the Baptist in Pichkhovani, the Argokhi Kvelatsminda Hall Church, the Ghvtaeba Monastery Complex in Akhmeta, and many other early Christian masterpieces. This creative heritage is vividly reflected in the 8th-11th century historic Kvetera fortress city, which became a prominent center of the Principality of Kakheti. The revival that started in Kvetera ultimately reached its pinnacle in the 11th century, when the cornerstone of Georgian history, culture, and religion—the Alaverdi Monastery—was consecrated. Beyond churches and monasteries, Akhmeta’s lands also display a vast array of diverse dwellings, towers, and fortresses, exemplified by the unique architectural phenomenon of the “tower-winery.” In the courtyard of the Zemo Khodasheni Monastery stands the “Fortress-Cellar,” built between 1760-1784. This structure served simultaneously as a defensive building, monk’s residence, and wine cellar, equipped with wine presses and more than twenty clay vessels buried in the ground. From the late medieval period, true fortifications became increasingly common across the Akhmeta region. One such prominent example of this legacy is the Pankisi Fortress, built on a high mountain overlooking the unmatched beauty of the Pankisi Gorge. With its massive fortress walls, it served as the center of the Pankisi Duchy in the developed Middle Ages, often finding itself in the fiery storms of regional conflicts. The list of Akhmeta’s fortresses and towers also includes the legendary towers of Bakhtrioni, those of the Cholokashvili family fortifications, and the stone towers built in the remote peaks of Tusheti, resembling swallows’ nests on the cliffs. Overall, Akhmeta’s architecture tells the story of a nation’s turbulent historical past and its struggle to maintain its unique culture amidst the cycles of survival and rebirth.

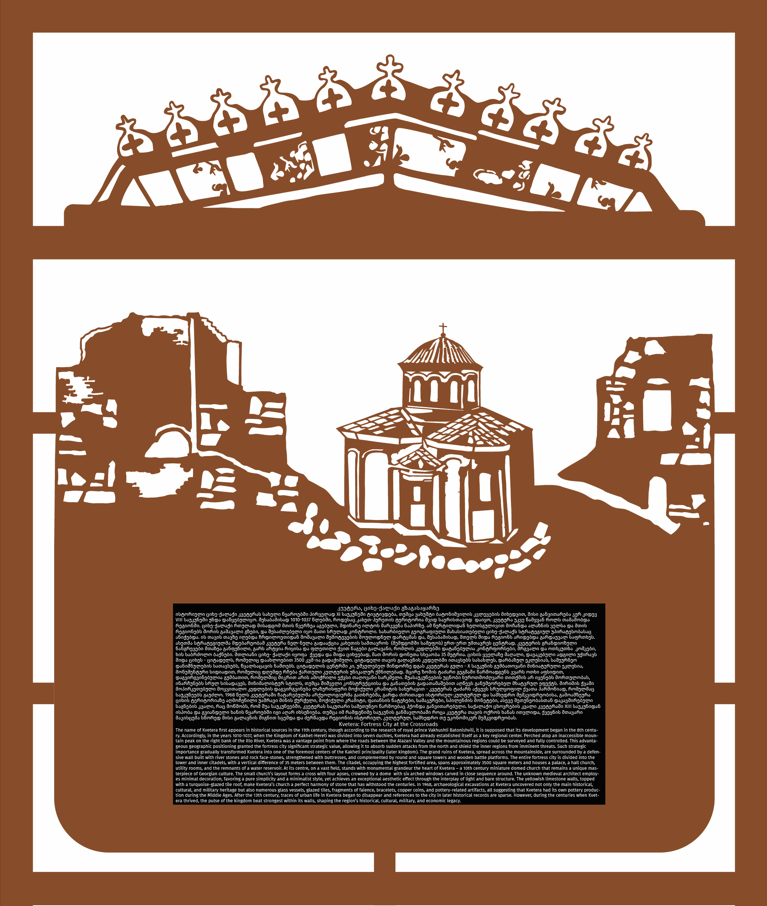

Kvetera: Fortress City at the Crossroads

The name of Kvetera first appears in historical sources in the 11th century, though according to the research of royal prince Vakhushti Batonishvili, it is supposed that its development began in the 8th century. Accordingly, in the years 1010-1037, when the Kingdom of Kakhet-Hereti was divided into seven duchies, Kvetera had already established itself as a key regional center. Perched atop an inaccessible mountain peak on the right bank of the Ilto River, Kvetera was a vantage point from where the roads between the Alazani Valley and the mountainous regions could be surveyed and fully controlled. This advantageous geographic positioning granted the fortress city significant strategic value, allowing it to absorb sudden attacks from the north and shield the inner regions from imminent threats. Such strategic importance gradually transformed Kvetera into one of the foremost centers of the Kakheti principality (later kingdom). The grand ruins of Kvetera, spread across the mountainside, are surrounded by a defensive wall built with river stones and rock face-stones, strengthened with buttresses, and complemented by round and square towers and wooden battle platforms. The entire fortress-city is divided into the lower and inner citadels, with vertical difference of 35 meters between them. The citadel, occupying the highest fortified area, spans approximately 3500 square meters and houses a palace, a hall church, utility rooms, and the remnants of a water reservoir. At its centre, on a vast field, stands with monumental grandeur the heart of Kvetera – a 10th century miniature domed church that remains a unique masterpiece of Georgian culture. The small church’s layout forms a cross with four apses, crowned by a dome with six arched windows carved in close sequence around. The unknown medieval architect employes minimal decoration, favoring a pure simplicity and a minimalist style, yet achieves an exceptional aesthetic effect through the interplay of light and bare structure. The yellowish limestone walls, topped with a turquoise-glazed tile roof, make Kvetera’s church a perfect harmony of stone that has withstood the centuries. In 1968, archaeological excavations at Kvetera uncovered not only the main historical, cultural, and military heritage but also numerous glass vessels, glazed tiles, fragments of faience, bracelets, copper coins, and pottery-related artifacts, all suggesting that Kvetera had its own pottery production during the Middle Ages. After the 13th century, traces of urban life in Kvetera began to disappear and references to the city in later historical records are sparse. However, during the centuries when Kvetera thrived, the pulse of the kingdom beat strongest within its walls, shaping the region’s historical, cultural, military, and economic legacy.

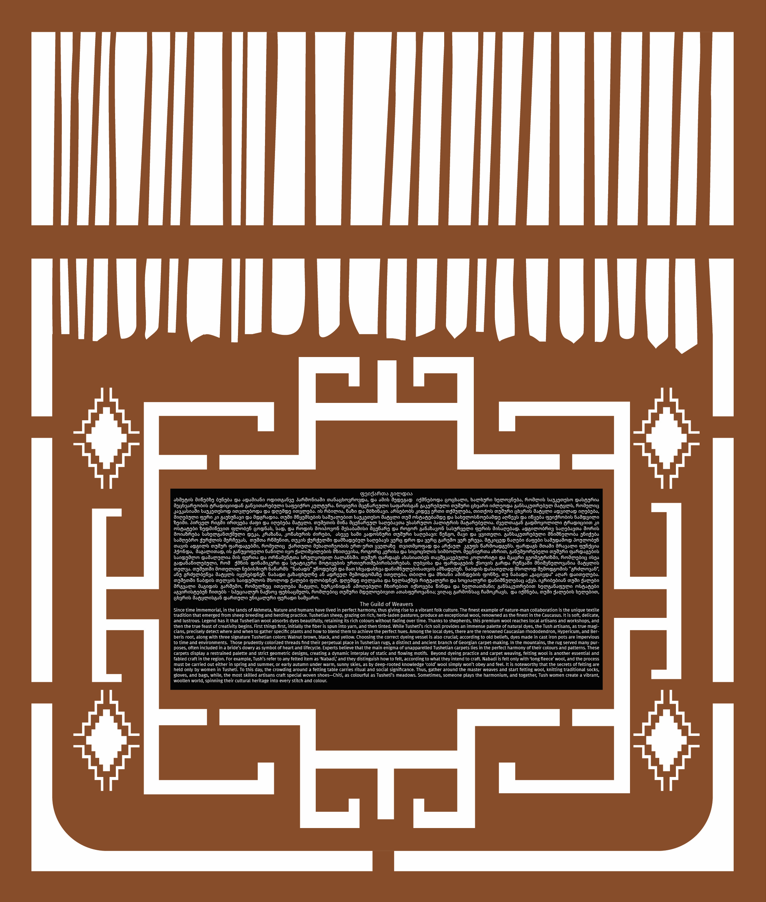

The Guild of Weavers

Since time immemorial, in the lands of Akhmeta, the Nature and the Human have lived in perfect harmony, thus giving rise to a vibrant folk culture. The finest example of nature-man collaboration is the unique textile tradition that emerged from sheep breeding and herding practice. Tushetian sheep, grazing on rich, herb-laden pastures, produce an exceptional wool, renowned as the finest in the Caucasus. It is soft, delicate, and lustrous. Legend has it that Tushetian wool absorbs dyes beautifully, retaining its rich colours without fading over time. Thanks to shepherds, this premium wool reaches local artisans and workshops, and then the true feast of creativity begins. First things first, initially the fiber is spun into yarn, and then tinted. While Tusheti’s rich soil provides an immense palette of natural dyes, the Tush artisans, as true magicians, precisely detect where and when to gather specific plants and how to blend them to achieve the perfect hues. Among the local dyes there are the renowned Caucasian rhododendron, Hypericum, and Berberis root, along with three signature Tushetian colors: Walnut brown, black, and yellow. Choosing the correct dyeing vessel is also crucial; according to old beliefs, dyes made in cast iron pot are impervious to time and environments. Those prudently colorized threads find their perpetual place in Tushetian rugs, a distinct and ancient branch of Georgian carpet-making. In the mountains, rug served many purposes, often included in a bride’s dowry as symbol of hearth and lifecycle. Experts believe that the main enigma of unapparelled Tushetian carpets lies in the perfect harmony of their colours and patterns. These carpets display a restrained palette and strict geometric designs, creating a dynamic interplay of static and flowing motifs. Beyond dyeing practice and carpet weaving, felting wool is another essential and fabled craft in the region. For example, Tush’s refer to any felted item as ‘Nabadi,’ and they distinguish how to felt, according to what they intent to craft. Nabadi is felt only with ‘long fleece’ wool, and the process must be carried out either in spring and summer, or early autumn under warm, sunny skies, as by deep-rooted knowledge ‘cold’ wool simply won’t obey and felt. It is noteworthy that the secrets of felting are held only by women in Tusheti. To this day, the crowding around a felting table carries ritual and social significance. Thus, gather around the master weaves and start felting wool, knitting traditional socks, gloves and bags, while, the most skilled artisans craft special woven shoes—Chiti, as colourful as Tusheti’s meadows. Sometimes, someone plays the harmonium, and together, Tush women create a vibrant, woollen world, spinning their own cultural heritage into every stitch and colour.

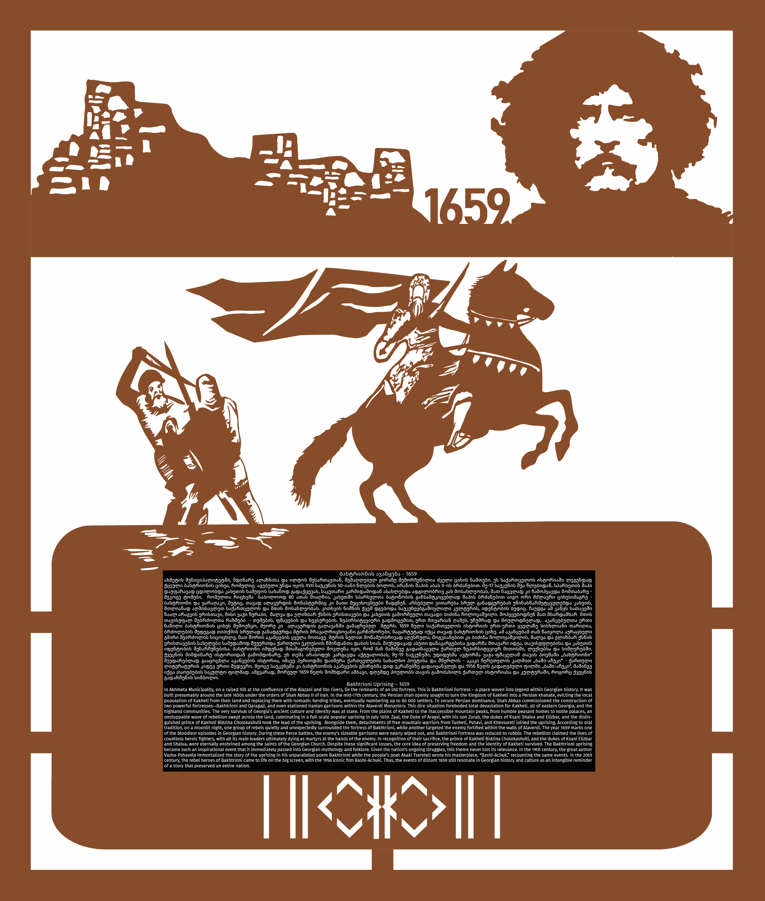

Bakhtrioni Uprising – 1659

In Akhmeta Municipality, on a raised hill at the confluence of the Alazani and Ilto rivers, lie the remnants of an old fortress. This is Bakhtrioni Fortress – a place woven into legend within Georgian history. It was built presumably around the late 1650s under the orders of Shah Abbas II of Iran. In the mid-17th century, the Persian shah openly sought to turn the Kingdom of Kakheti into a Persian khanate, evicting the local population of Kakheti from their land and replacing them with nomadic herding tribes, eventually numbering up to 80 000 settlers. To secure Persian dominance, Shah Abbas commissioned the construction of two powerful fortresses—Bakhtrioni and Qaragaji, and even stationed Iranian garrisons within the Alaverdi Monastery. This dire situation foreboded total devastation for Kakheti, all of eastern Georgia, and the highland communities. The very survival of Georgia’s ancient culture and identity was at stake. From the plains of Kakheti to the inaccessible mountain peaks, from humble peasant homes to noble palaces, an unstoppable wave of rebellion swept across the land, culminating in a full-scale common uprising in the month of July 1659. Zaal, the duke of Aragvi, with his son Zurab, the dukes of Ksani Shalva and Elizbar, and the distinguished prince of Kakheti Bidzina Cholokashvili took the lead of the uprising. Alongside them, detachments of free mountain warriors from Tusheti, Pshavi, and Khevsureti joined the uprising. According to oral tradition, on a moonlit night, one group of rebels quietly and unexpectedly surrounded the fortress of Bakhtrioni, while another targeted the enemy fortified within the walls of Alaverdi. The year 1659 marks one of the bloodiest episodes in Georgian history. During these fierce battles, the enemy’s sizeable garrisons were nearly wiped out, and Bakhtrioni Fortress was reduced to rubble. The rebellion claimed the lives of countless heroic fighters, with all its main leaders ultimately dying as martyrs at the hands of the enemy. In recognition of their sacrifice, the prince of Kakheti Bidzina Cholokashvili, and the dukes of Ksani Elizbar and Shalva, were eternally enshrined among the saints of the Georgian Church. Despite these significant losses, the core idea of preserving freedom and the identity of Kakheti survived. The Bakhtrioni uprising became such an inspirational event that it immediately passed into Georgian mythology and folklore. Given the nation’s ongoing struggles, this theme never lost its relevance. In the 19th century, the great author Vazha-Pshavela immortalized the story of the uprising in his unparalleled poem ‘Bakhtrioni’ while the people’s poet Akaki Tsereteli wrote his masterpiece, ‘Bashi-Achuk’, recounting the same events. In the 20th century, the rebel heroes of Bakhtrioni came to life on the big screen, with the 1956 iconic film Bashi-Achuki. Thus, the events of distant 1659 still resonate in Georgian history and culture as an intangible reminder of a story that preserved an entire nation.

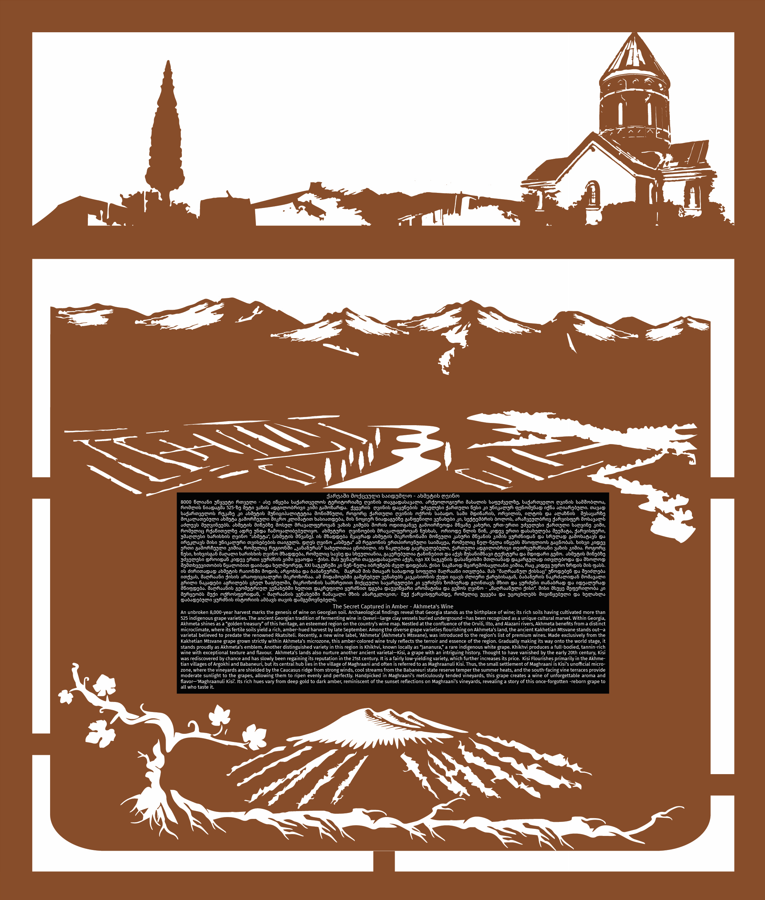

The Secret Captured in Amber – Akhmeta’s Wine

An unbroken 8,000-year harvest marks the genesis of wine on Georgian soil. Archaeological findings reveal that Georgia stands as the birthplace of wine; its rich soils having cultivated more than 525 indigenous grape varieties. The ancient Georgian tradition of fermenting wine in Qvevri—large clay vessels buried underground—has been recognized as a unique cultural marvel. Within Georgia, Akhmeta shines as a “golden treasury” of this heritage, an esteemed region on the country’s wine map. Nestled at the confluence of the Orvili, Ilto, and Alazani rivers, Akhmeta benefits from a distinct microclimate, where its fertile soils yield a rich, amber-hued harvest by late September. Among the diverse grape varieties flourishing on Akhmeta’s land, the ancient Kakhetian Mtsvane stands out—a varietal believed to predate the renowned Rkatsiteli. Recently, a new wine label, ‘Akhmeta’ (Akhmeta’s Mtsvane), was introduced to the region’s list of premium wines. Made exclusively from the Kakhetian Mtsvane grape grown strictly within Akhmeta’s microzone, this amber-colored wine truly reflects the terroir and essence of the region. Gradually making its way onto the world stage, it stands proudly as Akhmeta’s emblem. Another distinguished variety in this region is Khikhvi, known locally as “Jananura,” a rare indigenous white grape. Khikhvi produces a full-bodied, tannin-rich wine with exceptional texture and flavour. Akhmeta’s lands also nurture another ancient varietal—Kisi, a grape with an intriguing history. Thought to have vanished by the early 20th century, Kisi was rediscovered by chance and has slowly been regaining its reputation in the 21st century. It is fairly low-yielding variety, which further increases its price. Kisi Flourishes primarily in the Akhmetian villages of Argokhi and Babaneuri, but its central hub lies in the village of Maghraani and often is referred as Maghraanuli Kisi. Thus, the small settlement of Maghraani is Kisi’s unofficial microzone, where the vineyards are shielded by the Caucasus ridge from strong winds, cool streams from the Babaneuri state reserve temper the summer heats, and the south-facing vine terraces provide moderate sunlight to the grapes, allowing them to ripen evenly and perfectly. Handpicked in Maghraani’s meticulously tended vineyards, this grape creates a wine of unforgettable aroma and flavor—’Maghraanuli Kisi’. Its rich hues vary from deep gold to dark amber, reminiscent of the sunset reflections on Maghraani’s vineyards, revealing a story of this once-forgotten -reborn grape to all who taste it.

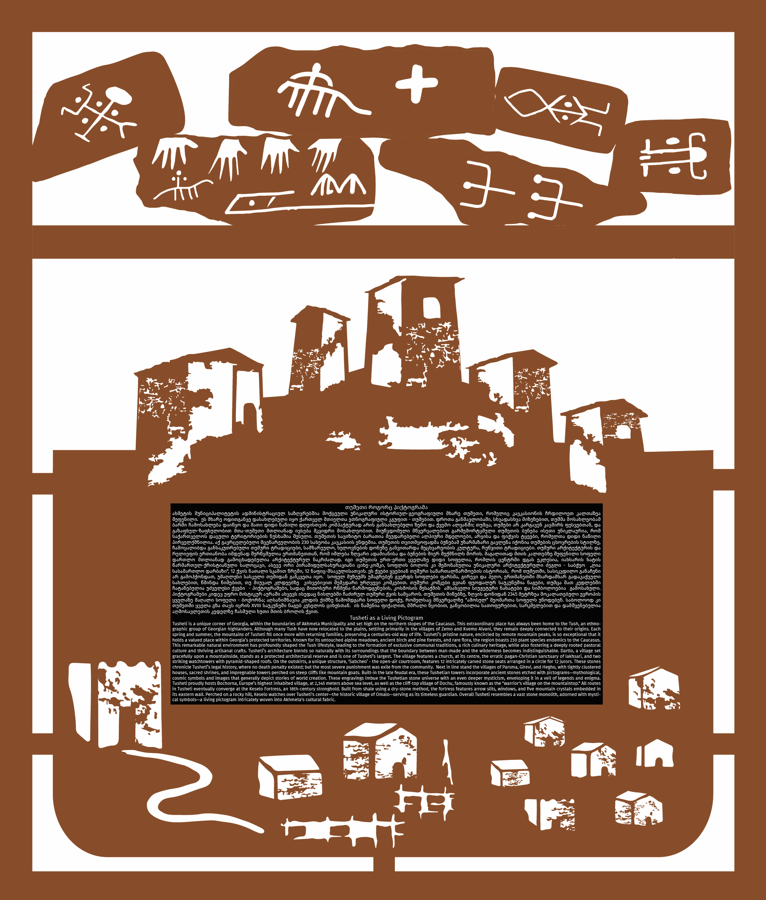

Tusheti as a Living Pictogram

Tusheti is a unique corner of Georgia, within the boundaries of Akhmeta Municipality and set high on the northern slopes of the Caucasus. This extraordinary place has always been home to the Tush, an ethnographic group of Georgian highlanders. Although many Tush have now relocated to the plains, settling primarily in the villages of Zemo and Kvemo Alvani, they remain deeply connected to their origins. Each spring and summer, the mountains of Tusheti fill once more with returning families, preserving a centuries-old way of life. Tusheti’s pristine nature, encircled by remote mountain peaks, is so exceptional that it holds a valued place within Georgia’s protected territories. Known for its untouched alpine meadows, ancient birch and pine forests, and rare flora, the region boasts 230 plant species endemics to the Caucasus. This remarkable natural environment has profoundly shaped the Tush lifestyle, leading to the formation of exclusive communal traditions, rich culinary heritage, while also fostering a deeply rooted pastoral culture and thriving artisanal crafts. Tusheti’s architecture blends so naturally with its surroundings that the boundary between man-made and the wilderness becomes indistinguishable. Dartlo, a village set gracefully upon a mountainside, stands as a protected architectural reserve and is one of Tusheti’s largest. The village is featuring a church, at its centre, the erratic pagan-Christian sanctuary of Iakhsari, and two striking watchtowers with pyramid-shaped roofs. On the outskirts, a unique structure, ‘Sabcheo’ – the open-air courtroom, features 12 intricately carved stone seats arranged in a circle for 12 jurors. These stones chronicle Tusheti’s legal history, where no death penalty existed; but the most severe punishment was exile from the community. Next in line stand the villages of Parsma, Girevi, and Hegho, with tightly clustered houses, sacred shrines, and impregnable towers perched on steep cliffs like mountain goats. Built in the late feudal era, these Tushetian towers incorporate ancient stones etched with pictograms—mythological, cosmic symbols and images that generally depict stories of world creation. These engravings imbue the Tushetian stone universe with an even deeper mysticism, enveloping it in a veil of legends and enigma. Tusheti proudly hosts Bochorna, Europe’s highest inhabited village, at 2,345 meters above sea level, as well as the cliff-top village of Dochu, famously known as the “warrior’s village on the mountaintop.” All routes in Tusheti eventually converge at the Keselo Fortress, an 18th-century stronghold. Built from shale using a dry-stone method, the fortress features arrow slits, windows, and five mountain crystals embedded in its eastern wall. Perched on a rocky hill, Keselo watches over Tusheti’s center—the historic village of Omalo—serving as its timeless guardian. Overall Tusheti resembles a vast stone monolith, adorned with mystical symbols—a living pictogram intricately woven into Akhmeta’s cultural fabric.

Discourse of Flavours

In the multicultural landscape of Akhmeta, Georgians, Ossetians, Kists, Chechens, and relocated Pshavi and Khevsuri communities have, over centuries, shaped a unique culinary heritage. Akhmeta’s cuisine is infused with the deep-rooted flavors of Kakheti, offering treasures like Mtsvadi – pork barbeque grilled over vine branches, the savory lamb Chakapuli simmered in aromatic herbs, and the beloved Khinkali dumplings. Akhmetan kitchens bring together culinary traditions that not only highlight diverse tastes and origins but also feature distinct preparation techniques that add a layer of authenticity to each dish. Consider, for instance, the Pshavian Dambalkhacho – a delicacy made from salted cheese curds, carefully dried over a central fire, then aged in clay pots for 1.5 to 2 months until it develops a unique “noble mold” on its surface. Akhmetian ‘sufras’ (dinner tables) also showcase Kist specialties such as the historic Jijig-galnish, a harmonious blend of meat and dough, along with the traditional Siskal-nekch. Another local gem is Choban-kaurma, or shepherd’s kaurma. Small lamb pieces are placed in a sheepskin bag, buried in an earthen pit by shepherds, then covered with soil and heated from above, allowing the meat to “braise” slowly within the ground. This culinary palette is further enriched by the distinctive dishes and drinks crafted within Tusheti’s stone homes. Visitors to Tushetian sacred sites may be offered Aludi, a ritual drink brewed from barley malt. The Tush people have carefully conserved certain recipes for centuries, for example every local knows how to prepare Khakhi—specially preserved meat to endure the long, cold winters, Tushs’ are also high masters at making yeast-free breads like Khmiadi, Gordila, Mosmula, and Katori—ultra-thin bread cake, similar to Khachapuri, filled with a molten blend of butter and cottage cheese. A highlight of this cuisine is Guda Cheese, a truly fascinating product in whole Georgian, and global gastronomy. Its journey is intricate: from the milking of sheep to warming the curd in Nabadi (traditional felted coat) and placing it into a sheepskin sack- Guda, each stage follows a precise, hour-calculated process. Finally, the cheese begins a maturation and ripping period within the Guda, which lasts approximately sixty days, transforming it into a delicacy with unmatched flavor and character. And at last but not least, the crowning jewel of Akhmetian gastronomy is ‘The Complete Cuisine’, a culinary book published in 1874 by an extraordinary woman from the village of Kistauri in Akhmeta—Barbara Jorjadze, a writer and passionate advocate for women’s rights. Since its release, the book has become a bestseller and endures as one of the most comprehensive culinary anthologies, encompassing the full treasury of Georgian cuisine.

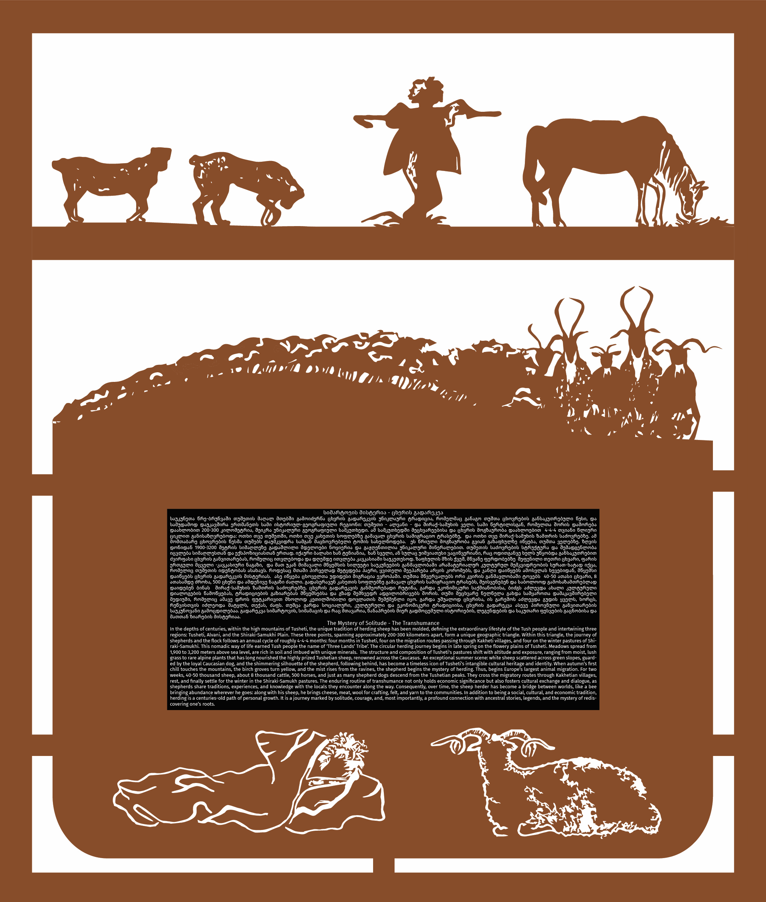

The Mystery of Solitude – The Transhumance

In the depths of centuries, within the high mountains of Tusheti, the unique tradition of herding sheep has been molded, defining the extraordinary lifestyle of the Tush people and intertwining three regions: Tusheti, Alvani, and the Shiraki-Samukhi Plain. These three points, spanning approximately 200-300 kilometers apart, form a unique geographic triangle. Within this triangle, the journey of shepherds and the flock follows an annual cycle of roughly 4-4-4 months: four months in Tusheti, four on the migration routes passing through Kakheti villages, and four on the winter pastures of Shiraki-Samukhi. This nomadic way of life earned Tush people the name of ‘Three Lands’ Tribe’. The circular herding journey begins in late spring on the flowery plains of Tusheti. Meadows spread from 1,900 to 3,200 meters above sea level, are rich in soil and imbued with unique minerals. The structure and composition of Tusheti’s pastures shift with altitude and exposure, ranging from moist, lush grass to rare alpine plants that has long nourished the highly prized Tushetian sheep, renowned across the Caucasus. An exceptional summer scene: white sheep scattered across green slopes, guarded by the loyal Caucasian dog, and the shimmering silhouette of the shepherd, following behind, has become a timeless icon of Tusheti’s intangible cultural heritage and identity. When autumn’s first chill touches the mountains, the birch groves turn yellow, and the mist rises from the ravines, the shepherd begins the mystery of herding. Thus, begins Europe’s largest animal migration. For two weeks, 40-50 thousand sheep, about 8 thousand cattle, 500 horses, and just as many shepherd dogs descend from the Tushetian peaks. They cross the migratory routes through Kakhetian villages, rest, and finally settle for the winter in the Shiraki-Samukh pastures. The enduring routine of transhumance not only holds economic significance but also fosters cultural exchange and dialogue, as shepherds share traditions, experiences and knowledge with the locals they encounter along the way. Consequently, over time, the sheep herder has become a bridge between worlds, like a bee bringing abundance wherever he goes: along with his sheep, he brings cheese, meat, wool for crafting, felt, and yarn to the communities. In addition to being a social, cultural, and economic tradition, the herding is a centuries-old path of personal growth. It is a journey marked by solitude, courage, and, most importantly, a profound connection with ancestral stories, legends, and the mystery of rediscovering one’s roots.

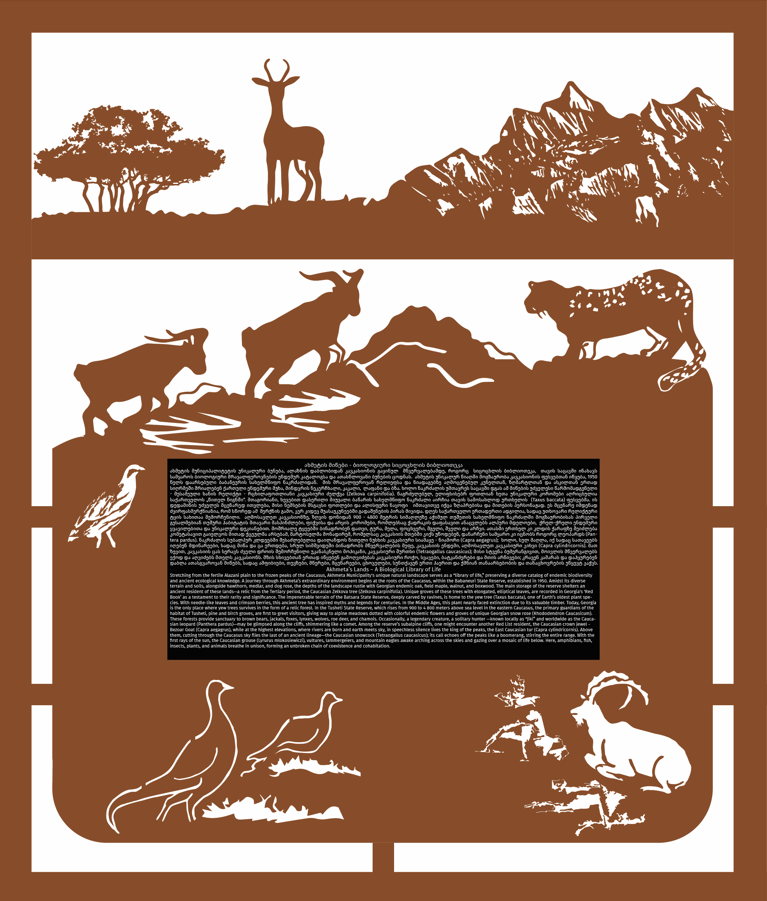

Akhmeta’s Lands – A Biological Library of Life

Stretching from the fertile Alazani plain to the frozen peaks of the Caucasus, Akhmeta Municipality’s unique natural landscape serves as a “library of life,” preserving a diverse catalog of endemic biodiversity and ancient ecological knowledge. A journey through Akhmeta’s extraordinary environment begins at the roots of the Caucasus, within the Babaneuri State Reserve, established in 1950. Amidst its diverse terrain and soils, alongside hawthorn, medlar, and dog rose, the depths of the landscape rustle with Georgian endemic oak, field maple, walnut and boxwood. The main storage of the reserve shelters an ancient resident of these lands—a relic from the Tertiary period, the Caucasian Zelkova tree (Zelkova carpinifolia). Unique groves of these trees with elongated, elliptical leaves, are recorded in Georgia’s ‘Red Book’ as a testament to their rarity and significance. The impenetrable terrain of the Batsara State Reserve, deeply carved by ravines, is home to the yew-tree (Taxus baccata), one of Earth’s oldest plant species. With needle-like leaves and crimson berries, this ancient tree has inspired myths and legends for centuries. In the Middle Ages this plant nearly faced extinction due to its valuable timber. Today, Georgia is the only place where yew-tree survives in the form of a relic forest. In the Tusheti State Reserve, which rises from 900 to 4 800 meters above sea level in the eastern Caucasus, the primary guardians of the habitat of Tusheti, pine and birch groves, are first to greet visitors, giving way to alpine meadows dotted with colourful endemic flowers and groves of unique Georgian snow rose (Rhododendron Caucasicum). These forests provide sanctuary to brown bears, jackals, foxes, lynxes, wolves, roe deer, and chamois. Occasionally, a legendary creature, a solitary hunter —known locally as “Jiki” and worldwide as the Caucasian leopard (Panthera pardus)—may be glimpsed along the cliffs, shimmering like a comet. Among the reserve’s subalpine cliffs, one might encounter another Red List resident, the Caucasian crown jewel – Bezoar Goat (Capra aegagrus), while at the highest elevations, where rivers are born and earth meets sky, in speechless silence lives the king of the peaks, the East Caucasian tur (Capra cylindricornis). Above them, cutting through the Caucasus sky, flies the last of an ancient lineage—the Caucasian snowcock (Tetraogallus caucasicus); its call echoes off the peaks like a boomerang, stirring the entire range. With the first rays of sun, the Caucasian grouse (Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi), vultures, lammergeiers, and mountain eagles awake arching across the skies and gazing over a mosaic of life below. Here, amphibians, fish, insects, plants, and animals breathe in unison, forming an unbroken chain of coexistence and cohabitation.